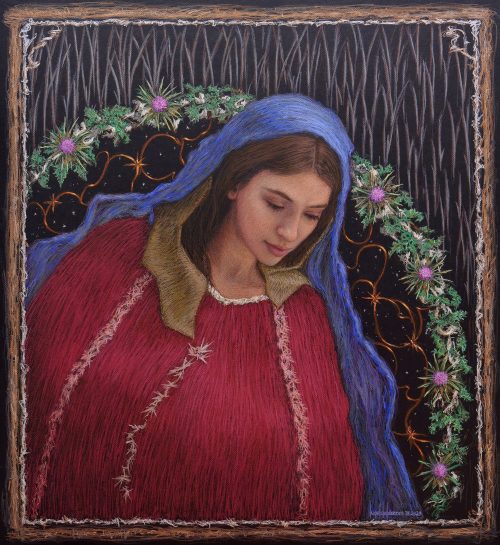

Portraits and Allegories

“When I work in a portrait everyday life mingles with signs of an imagined life. That is how I conceive the exercise of painting a portrait, building up at the same time what is real and what is imaginary, the form and the content, the figure and its imprint. That inner element, the spirit, should live in the canvas in the same way that it lives in the portrayed person. If the features, the limbs, the body in general, constitute the most demanding nature and the foundation of the harmonies, the imprint they leave on the retina when they vanish is its essence, that which endures and outlives them.

The allegory, understood as an abstraction that has just adopted specific forms, means to me the plastic transcription of the world of ideas, the projection of feelings through symbols, and therefore an ideal resource to complete what is strictly real.

Both disciplines, the portrait and the allegory, offer me the possibility of a setting that is tailored to the impulse, where observation transforms into signs, thought is hidden under the harmony, the chaos of dreams can be summarized in fictitious ornaments... All as an answer to a core idea: reason chases beauty in the same way that the portrait chases the interior of the person”.

The allegory, understood as an abstraction that has just adopted specific forms, means to me the plastic transcription of the world of ideas, the projection of feelings through symbols, and therefore an ideal resource to complete what is strictly real.

Both disciplines, the portrait and the allegory, offer me the possibility of a setting that is tailored to the impulse, where observation transforms into signs, thought is hidden under the harmony, the chaos of dreams can be summarized in fictitious ornaments... All as an answer to a core idea: reason chases beauty in the same way that the portrait chases the interior of the person”.

See more of this collection

See more of this collection

ZOOM

ZOOM

+ INFO

+ INFO